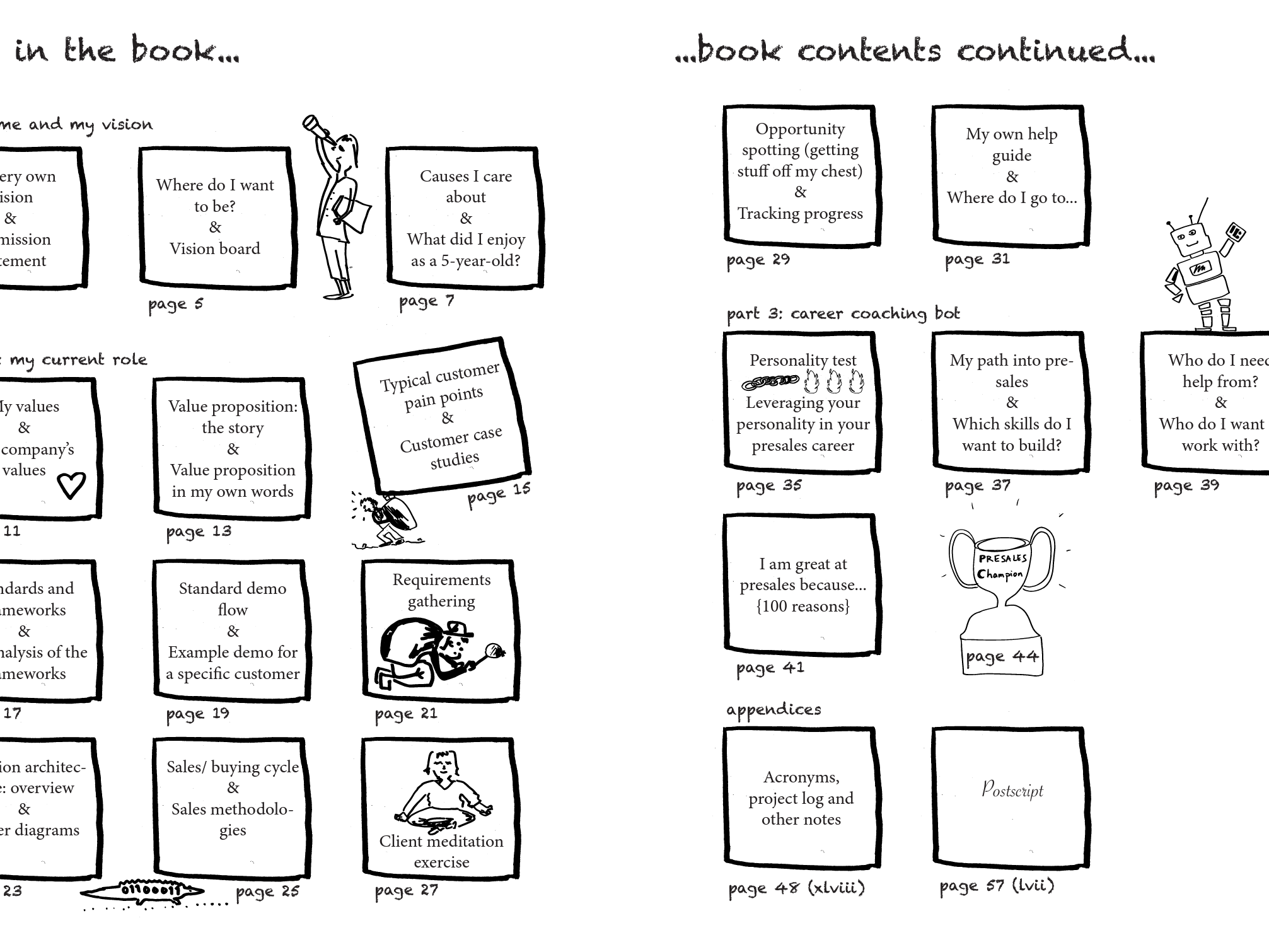

The research and applications of Digital Theology are still taking their first steps at the time of writing (2021). I created five illustrations of the book to bring alive the main points of this new area of research.

The project was very interesting, as it required a lot of analysis of the book text, and thinking how to visualise complex ideas in an accessible way.

The illustrations created with oil on canvas, finalised with Gimp and converted into greyscale for black and white printing.

Buy the book from Emerald.

Fig 5. Technology (left side of figure) and theology (right) share structural patterns, and inviting a natural framework for the study of digital theology. A program code includes the code itself, (top left), the meaning of the code, such as ‘printing’ (middle left), and relevant action which could be interpreted as the intended benefit to the user, such as receiving the message (bottom left). In theology, the format follows with the written creed (top right), the meaning of the creed, such as ‘Holy Spirit’ (middle right) and the act of faith, such as how the Holy Spirit inspires the individual to help others (bottom right).

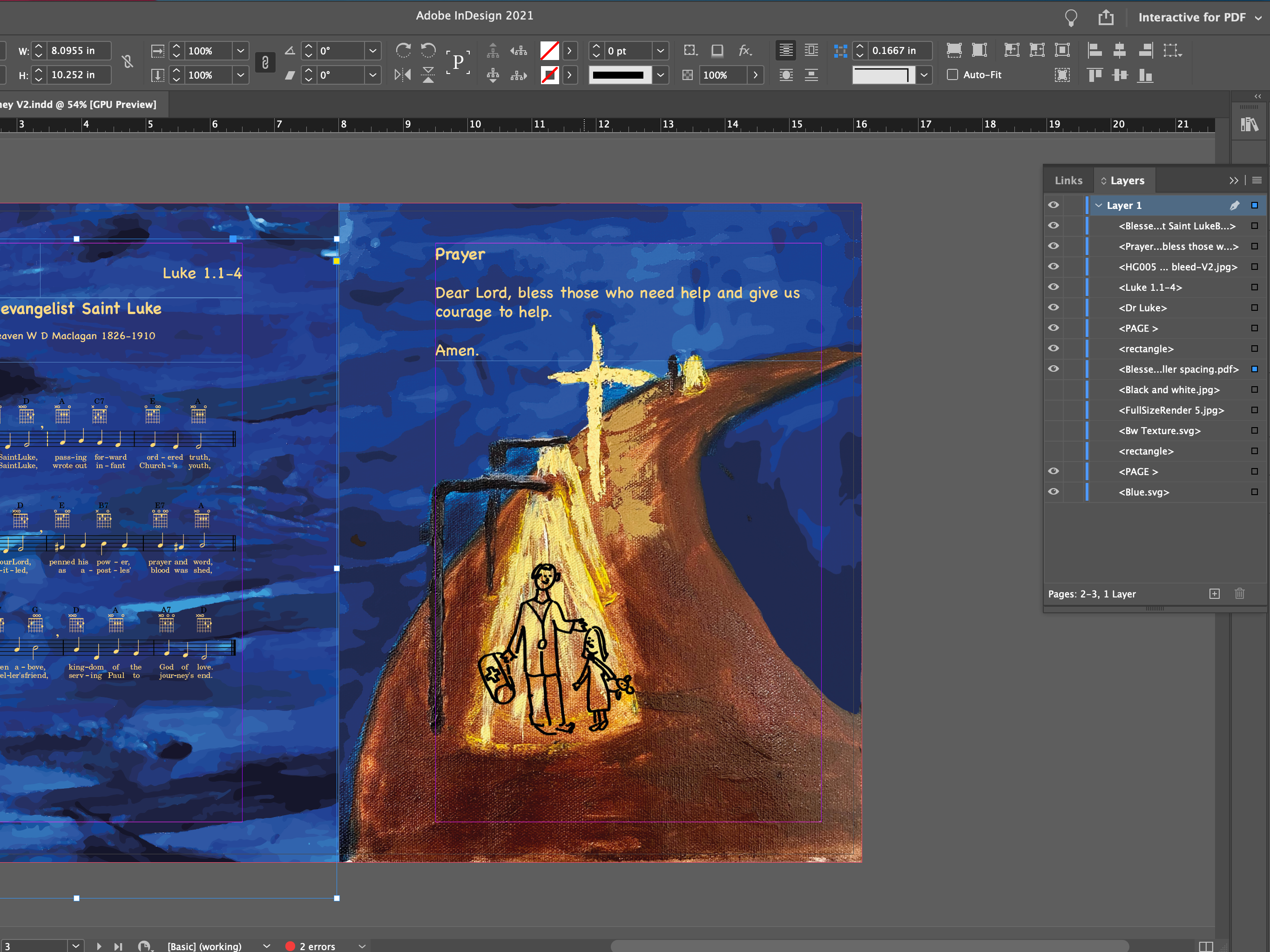

Fig 1. Future inventions of digital theology will most likely use some form of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies, requiring a radical shift in traditional establishments. For example, if receiving communion through your television will be possible, the Christian churches will need to discuss what aspects of it, if any, violate the current guidelines about the sacrament. Already, churches are using augmented reality headsets in their quest to visualize historical life. Various phone and tables apps help spread the message of churches, and allow users to interact, question, and comment on live stream worships.

Fig 2. Christian dating apps are an example of applied digital technologies that may shape mainstream, non-secular apps in the near future. Christian dating apps follow Christian ethics principles, for example by limiting the number of profiles you can browse each day. The limit reminds the user that they are connecting with real people, not just digitalized profiles. On the other hand, the users are protected from social overwhelm with this feature.

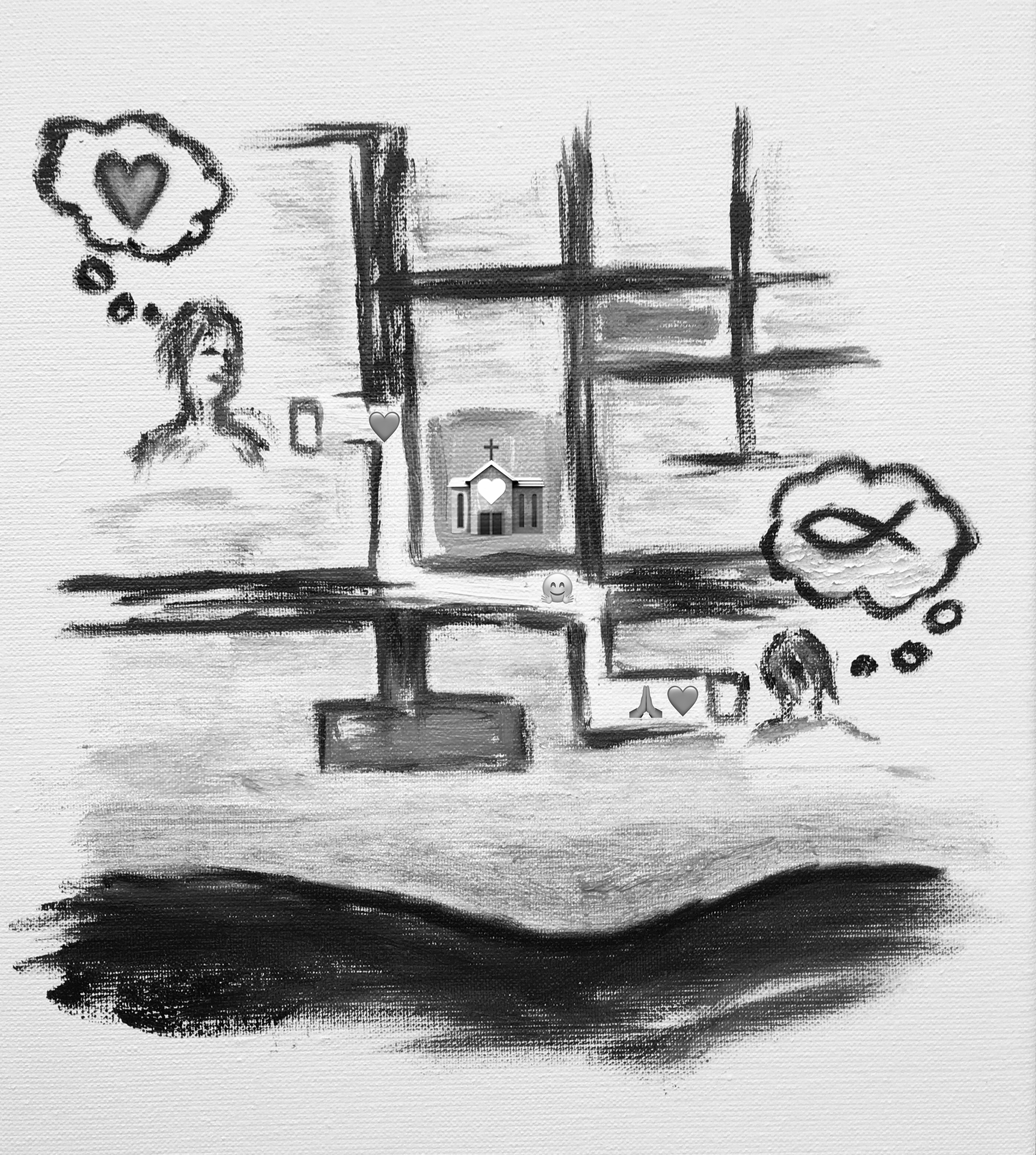

Fig 3. Spiricons, or spiritual emojis, allow people of faith to express themselves visually when sending messages on digital devices. Rather than using only text, including emojis is a more natural way of communicating for many. An emoji may have different meanings depending on its context, and its user. Furthermore, the message must be interpreted by its recipient who has their own frame of reference, and this can cause confusion or even tension. For example, the ‘pray’ emoji 🙏🏽 can replace both ‘thank you’, and ‘God bless’.

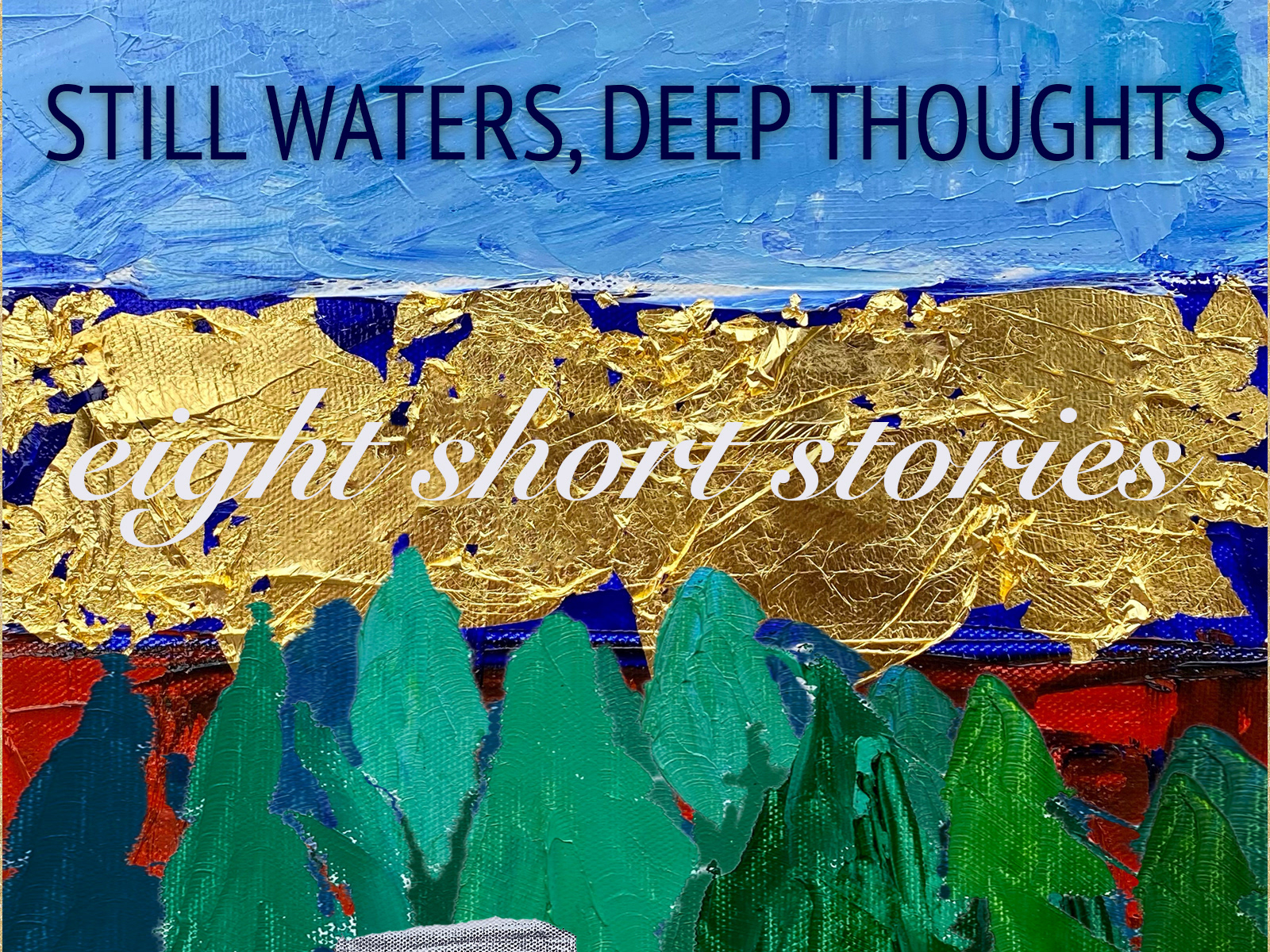

Fig 4. The strands of the double helix of theology and technology are intertwined in spiritual, digitally represented experiences. To illustrate this, Ann and Ben experience God’s presence in nature in connected yet distinct events. Ann’s Bible app recognizes the seaside images she is taking on a walk and suggests appropriate Bible verses for her reading. Ben’s recording of the rain in the forest, a holy space for many, is matched automatically to his musical composition, on his phone.